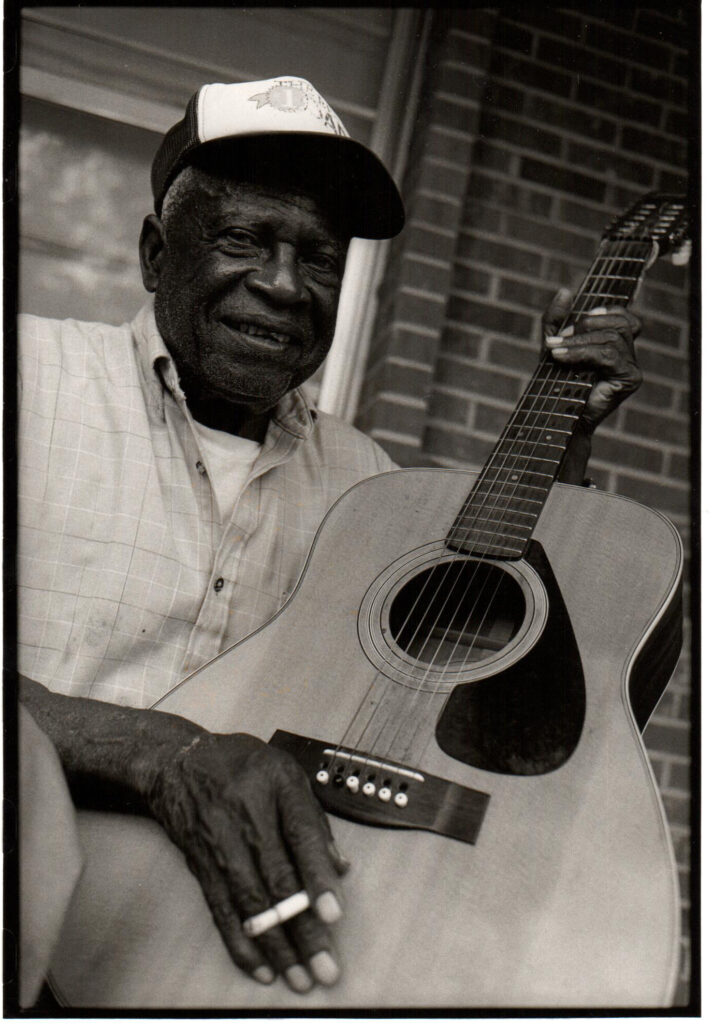

2015 Honoree

(1921-2003)

Country bluesman J. W. Warren was born in Enterprise, Alabama, on June 22nd, 1921, to John and Matilda Warren. One of eleven children, he worked most of his early life sharecropping with his family in Ariton, a tiny town in the heart of the Wiregrass region. Warren often spoke of the harsh conditions living in the Jim Crow South, of the severe poverty in which his family existed, scarcely eking out a living. Rarely attending school and barely able to read and write, he recalled, “I came up the hard way. I never had a break whatsoever. In other words…I was born in the wrong part of the world….” He noted that living through the great depression was “like slavery times.”

Warren’s first love was blues music, and he began in his teens to play guitar and sing, all the while working in the fields and later at a local sawmill. His mentors were local bluesmen Buck Stevens, Albert Williams, and especially brothers James L. and Johnny Haynes. Performing alone or with others, he played house parties and barbeques “for a few bucks and moonshine.”

Ariton was also the home of Big Mama Thornton, and Warren remembers her as a young harmonica player with whom he jammed when she was in her early teens. Warren commented, “She could blow it buddy! She could sing it too! That girl could blow that harp.”

At 22, Warren entered the military, serving through World War II, and was later stationed at Fort Rucker near Enterprise, Alabama. On leaving the service, he returned to Ariton, where he worked as a farmer and again played local jukes and house parties. His youngest brother Curtis also played guitar, and they often played together.

As a classic example of the backwoods, acoustic country blues style, Warren played two or three guitar parts, simultaneously picking out bass lines, rhythm, melody, and harmony. He used a variety of guitar tunings and was a stunning slide player, using an old jack knife for a slide. J. W. cited Blind Boy Fuller and Blind Blake as his greatest influences, along with Blind Lemon Jefferson, Buddy Moss, Peetie Wheatstraw, and Blind Willie Johnson, all heard on 78 records played on a Victrola his sister, Ruby, owned.

A blues storyteller with a raw, rough, yet warmly melodic vocal sound, his repertoire included a few original songs, such as “Hoboing My Way Into Hollywood,” “Destination Blues,” and “The Escape of Corinna,” and he performed traditional blues songs like “Rabbit on a Log,” “John Henry,” and “Careless Love” with his own unique flair. Influenced by the duo Rosetta Tharpe and Marie Knight, Warren also sang some gospel songs, which he sometimes played at the only local black Baptist Church, Mount Olive. Interestingly, this was the same church where Big Mama Thornton’s father had been preacher and where Thornton got her start.

In 1980, Warren was discovered by field researcher George Mitchell, who returned to Ariton to record Warren’s music in 1981 and 1982. Some of the resulting tracks were released on an LP called Bad Luck Bound on the Dutch Swingmaster label. Mitchell considered Warren’s song, “The Escape of Corinna,” a country blues masterpiece. The Music Maker Relief Foundation recorded Warren in 1994 and released several tracks on a number of anthologies. In 2005, the George Mitchell collection was re-released as a CD, titled Life Ain’t Worth Living, on Fat Possum Records.

Warren’s life was documented by German blues photographer and field researcher Axel Küstner, who visited with Warren every year between 1993 and 2003. According to Küstner, “J. W. was probably the last practitioner of a little documented Southeast Alabama blues guitar style that featured excellent finger picking and slide technique.”

Despite encouragement from a dedicated international following of folklorists and fans, Warren was reluctant to leave his hometown and declined invitations to perform elsewhere in the US or in Europe, and it is probably this lack of exposure to a wider audience that prevented his music from gaining the recognition it deserved. J. W. Warren died on August 5, 2003, in relative obscurity. He is buried at Travelers Rest Cemetery in Ozark and is survived by six children.

Warren epitomizes a once thriving, and largely undocumented, rural Wiregrass Alabama blues culture, the same environment that gave birth to other greats, such as Big Mama Thornton, Dan Pickett, John Lee, Johnie Lewis, Ed Bell, Ike Zinnerman, and many more. Thankfully, unlike so many Alabama blues musicians from his era, Warren’s haunting blues guitar and vocal sound live on in his recordings.